When is football no longer football?

- BFCN

- Sep 28, 2023

- 12 min read

Currently I am studying the MBP Master in High Performance Football. It's a course I first learned about in 2015. So many excellent coaches have completed it, and now I have the opportunity. This is one of several MBP courses I have done, including their Youth Soccer Expert course, which I undertook in Barcelona last year. As always, high quality, and very in depth.

At the start of this latest course, which is similar to a football studies degree course, we're learning about defining what football is. Perhaps philosophical in nature, but it is important to understand what the game is, to then understand the components that make football football. What are the systems that explain football, and how do they all work together?

MBP are very keen on representative practice design. Put simply, this is the idea that you get good at what you do, so we need to make sure what you do is what you do.

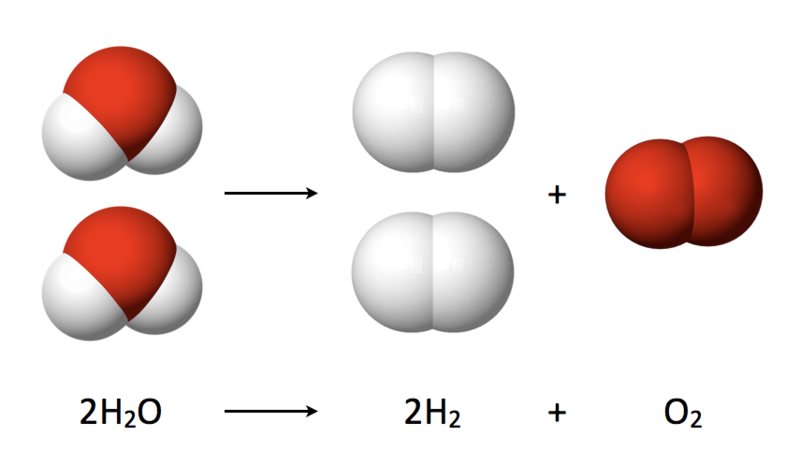

There was one slide during a presentation which put it as succinctly as possible, while also being thought provoking. They used water as a metaphor for football, and I'll take you on this journey real quick.

When is water no longer water?

The ocean is water, right? It's a lot of water. It's total water. And this represents the full game. But can sea water be reduced? And if so, is it still sea water?

Take a bottle and scoop up some water from the ocean. Is it still sea water? Of course, yes, but it's no longer part of the sea. However, a scientific analysis would conclude that it is sea water.

Next, we pour the water from the bottle into a glass. It's now smaller, and there is less of it, but it's still water, right? We can reduce it further and further.

Of course this drop is still water. But it's very far removed from the ocean. What makes water an ocean is the presence of other water.

If we reduce water down to a single molecule, two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom, that molecule is still water. How useful is it to us without the other molecules? If we split that molecule into the three atoms, it's no longer water, it's oxygen and hydrogen. Not useful to us if we want an ocean, and definitely not water.

The game is about pictures. Football is a series of problems, presented to us visually, with us trying to find those solutions.

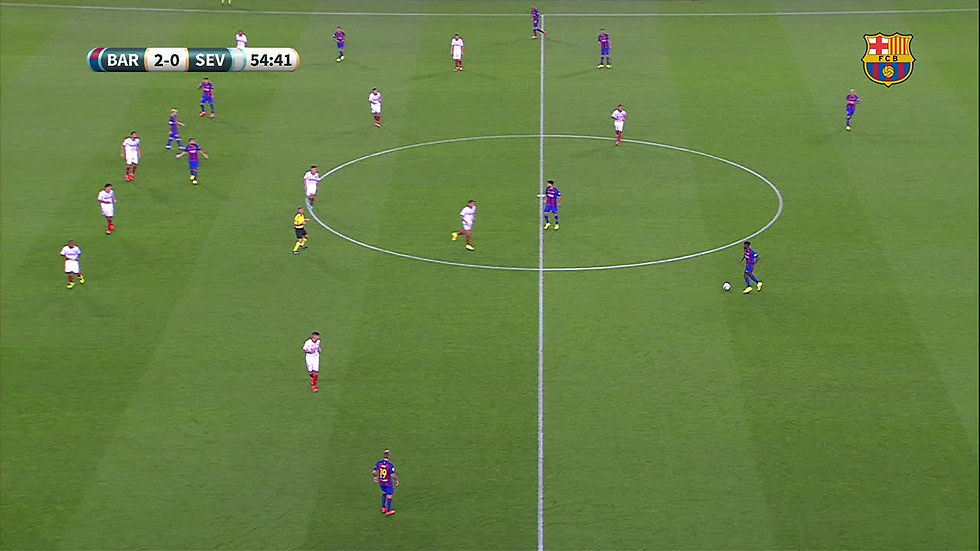

Busquets is looking up, taking in information visually, assessing the space, time, distances, opponents, teammates, and weighing up the risk and reward as he considers his options and what action to execute. This is what we mean when we talk about players taking pictures. He is scanning for information, taking mental snapshots.

If you're the ball carrier in this picture, what do you do? Everything must be considered within the context of the game. You're 2-0 up, in possession, ten minutes played in the second half. You're at home, the pitch is in good condition. The opposition are sitting off slightly, engaging at the halfway line, but also have a high line. Do you need to take risks at this point?

If you're the ball carrier, do you pass or dribble?

Dribble; forwards, backwards, left, right, or pause in place. Fast to take space, or slow to bait a press.

Pass; short or long? Back to the goalkeeper to draw the opposition higher? Left to 19 to shift the opposition laterally? Into the CDM who is almost marked in the centre circle to attract pressure and fix an opponent? Left has more space, but right has more options. You've also got three players in their back line, with a lot of space in behind. Do you hit one over the top for your teammates to run onto? Do you need to at this point in the game with this score line?

We know that all this is football, but how does this relate to practice design? The big question is this; how far can we reduce the game before learning transfer no longer occurs? Before it is no longer football.

When designing a practice, ask yourself this; are they learning the game, or are they learning the drill?

For me, as a player, if I was participating in a passing pattern like this, I think I'd be so focussed on who has to run where, and what pass goes to who, that my mental processing powers would be dedicated to remembering how the drill works, rather than getting better at football. Play would slow down as players would be having to think and remember. Touches would be bad because there's no defender to punish you. And intensity may be low because there's no competition, there's nothing to win.

If we take a staple of youth football, the tails game, where players tuck a bib into the back of their shorts like a tail. Players have a ball at their feet, and the defender has to pull the tail out of their shorts. This game teaches players to protect their bums, and show the ball, rather than protect the ball by showing their bum, which is what they should be doing in football.

See here? Protect the ball by showing your bum to the opponent. In the tails game, it teaches us the opposite. Therefore, players are learning the drill, but not the game. Does the training exercise reward behaviours that are both consistent with football, but also beneficial to perform within the game?

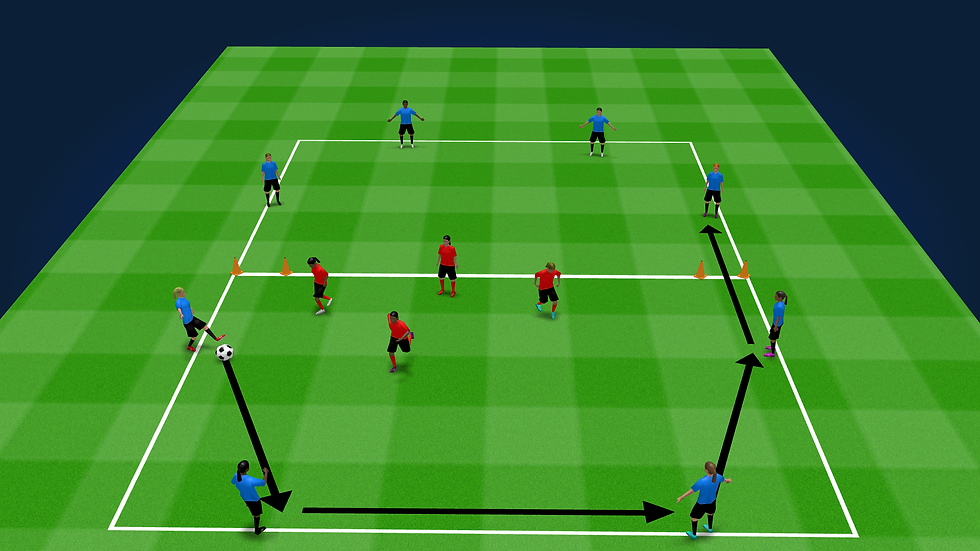

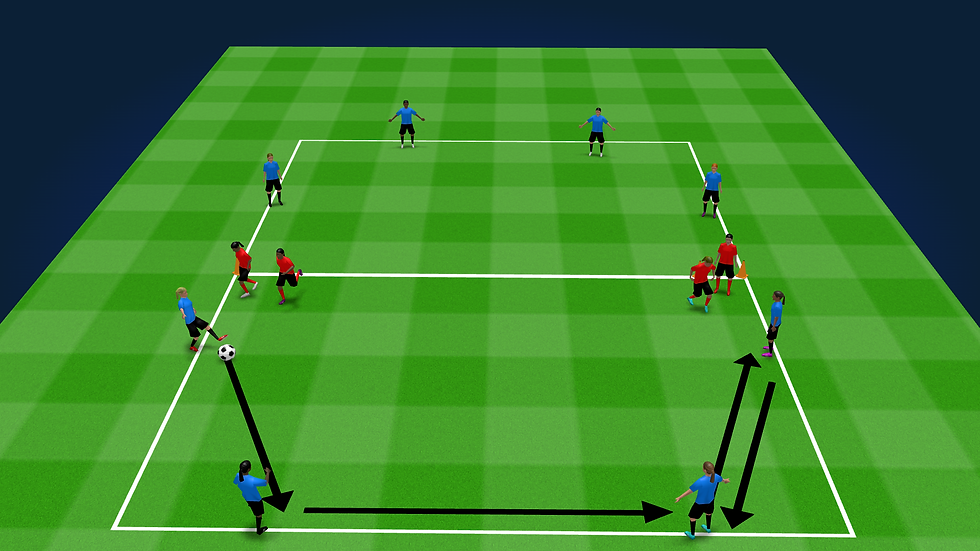

Have a look at the below exercise and see if you spot any issues with it.

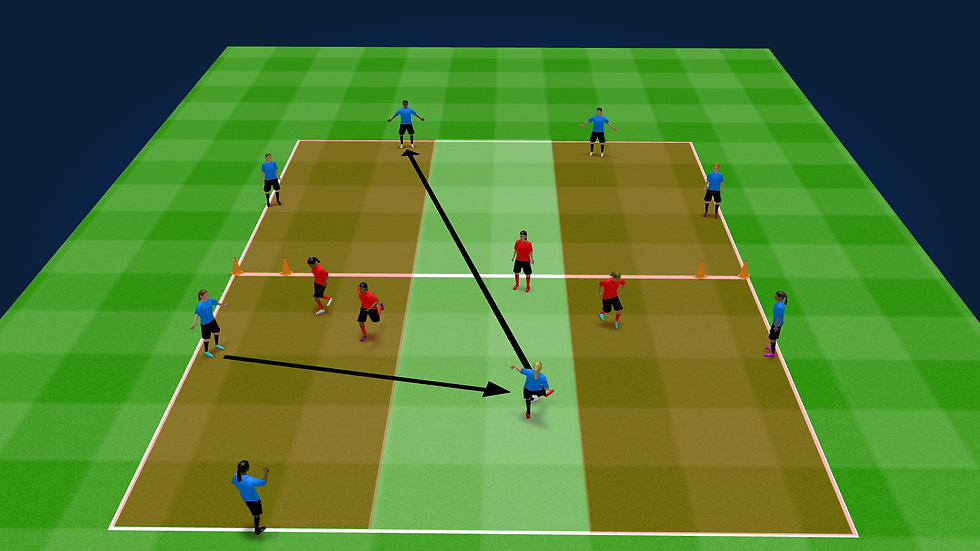

A former colleague of mine ran this exercise. He was working on switching play with an adult team. I'm not looking to dob in a former colleague, but the guy was also a sneaky, underhanded weasel, that caused several problems for me, so I don't mind taking a few shots online. It's a simple transfer game, one that there are millions of variations of, and we've done plenty of times.

His first mistake was that he didn't include a transition. If the defending team won the ball, the game stopped, and the team that lost possession became the defending team. Secondly, the opportunity to transfer was limited to only the small gates at the extremes of the area. The gates were about two yards wide, which could easily be blocked by one player. Thirdly, the possession team had to make four passes before they could play the ball forward. This meant that if ever there was an opportunity to play forward, despite the small goals, the team often had to make another pass or two before being able to play forward anyway. This allowed the defending team time to recover, and the gap to play forward was closed. Fourthly, there was no way to win. Nobody was getting any points or scoring any goals, so there was no incentive to work hard or play at game speed. The defending team had no way of scoring, and only a small area to protect, so they didn't need to come out and hunt for the ball.

Here's what happened.

The defending team just put two players in front of the gates. The possession team would pass the ball back and forth, unable to penetrate, and unable to exploit the massive space in the middle of the area, because the rules wouldn't allow it. They'd made their four passes, and still couldn't play forward. My colleague sensed something was wrong. His solution was to shout at them to work harder. "Demand more" for all you Football Manager players. But what could they do? The possession team were making their four passes and shifting the ball left and right, like they'd been instructed to do. The defending team were defending in a way that the drill required. It was unrealistic to football, but it was the type of defending the drill required. Meanwhile, the blues in the other half had gone five minutes without touching the ball. Occasionally, between interventions demanding more movement and more effort, my colleague would step in and boot the ball into the other half to give the other team a go. The same problems would occur, with the defending team blocking the gates, and players standing still.

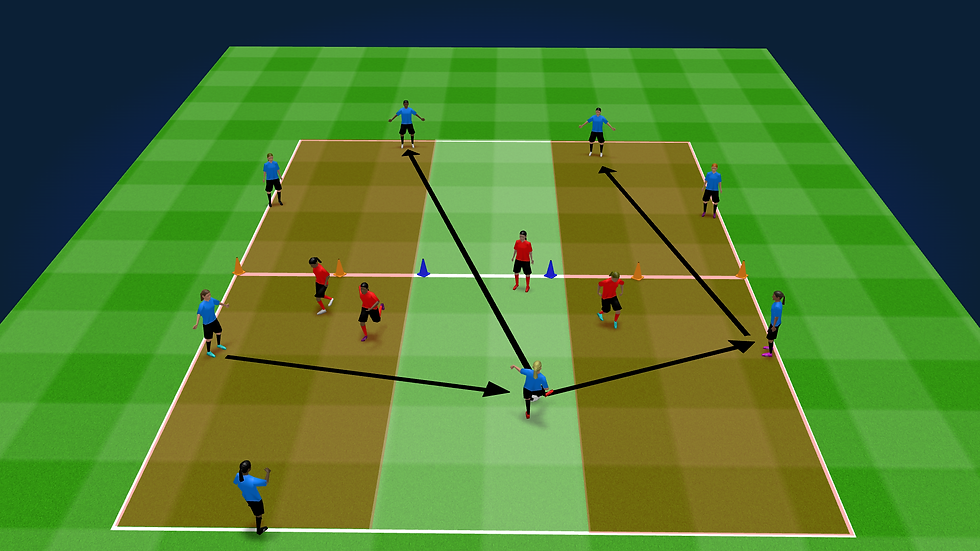

What this showed was not only poor practice design, but also a fundamental misunderstanding of what switching play is. Switching play isn't just shifting the ball from one side to the other. Perhaps a better phrase to use is changing the point of the attack. The ball can act as bait. It draws out the opposition and it moves them laterally as they look to press. So instead of thinking of a switch of play as a big shift from one extreme to another, think of it as moving the ball laterally until a way forward presents itself. Even if that lateral pass is only five or ten metres. We've changed the point of attack.

See in the above picture, we didn't need to switch the ball from far left to far right to find the forward pass. We just needed to move the ball a few yards to the right. Try to think of the pitch in vertical channels, maybe three, four, five, or six depending on your game model and match constraints. To switch the play (change the point of attack) you just need to move the ball from one channel to the next.

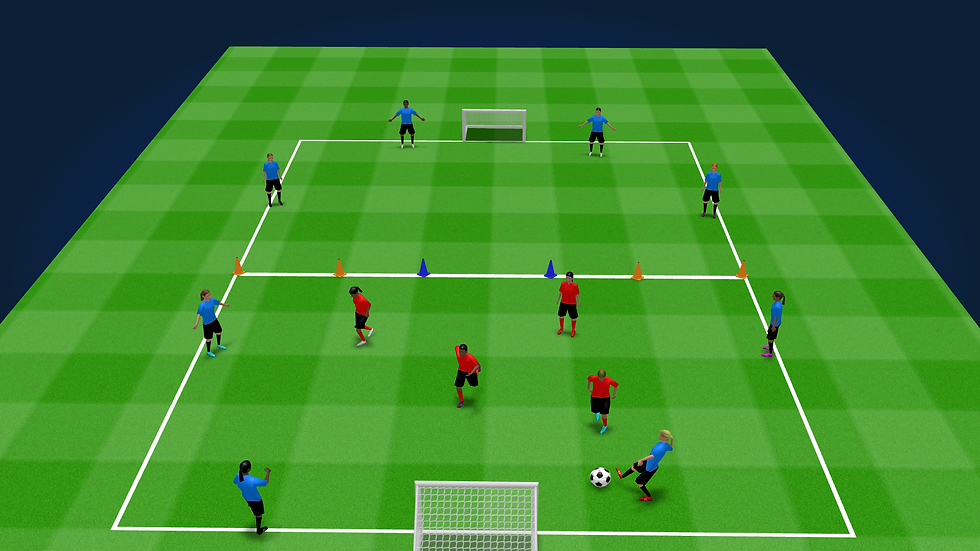

My first modification to my colleague's exercise would be to widen the gates, and add another gate in the middle. This means the ball can be sent forward in any of the three channels. If the gate is wide enough, it cannot be blocked by a single defender just standing in the way. This now means the defending team have to come out and press, as their cover shadow would block the gate while they hunt for the ball. The attacking team are rewarded playing short or long lateral passes. Longer passes can sometimes allow the opposition more time to recover. A short pass to a teammate in the middle channel with a forward passing option is much quicker.

My next move would be to remove the four passes before being allowed to play a forward pass. If it doesn't exist in the real game, we have to consider what benefit we get from including it in our practice. For me, the whole point of switching play is to move the opposition to exploit space. If we move the ball and create gaps in their shape, I want to be able to play that forward pass as quick as possible. If we have to make a couple more passes, due to the practice constraint, the opportunity to penetrate disappears.

The next thing I'd do is add a way for the defending team to score. This now encourages them to come out and press. Something like a goal, or smaller goals, or an end zone. By having a way to get points, teams play for more intensity. It also adds risk and reward to all decisions, with players having to factor in the danger associated with each action. A horizontal pass from the possession team is a pass across goal, which, if hit badly, could be a fatal error.

The modifications to this exercise make it more like football. The behaviours from the players are now way more realistic. They're not hitting pointless roadblocks. Any mistakes will come from technical or tactical errors, and can then be coached. Rather than shouting at them, begging for effort.

One of the best presentations on this topic I ever saw was Todd Beane of Tovo, just down the coast from my friends at MBP in Barcelona. It was the United Soccer Coaches Convention in 2019, hosted in Chicago.

The first 10-15 minutes of this presentation are pure gold. I can occasionally see myself in the audience on the far side in a grey hoodie. This talk turned out to be quite controversial. Todd suffered a lot of heat on Twitter, and several people walked out of the presentation in disgust. He was challenging established training paradigms. What many countries have been doing for years. What several very profitable clubs and organisations have been doing for a long time. It felt like Charles Darwin had walked into a room full of creationists.

The metaphor Todd uses is to break down cycling into its most fundamental parts; sitting on your ass, braking, pedalling, steering. Cycling is the water, these are the atoms that make up cycling. He said we teach all of these separately, and then assume that they can come together in the real competition. He also makes points about players leaving the game because this method is not fun, cutting players despite performance because they are too short, and then making selections based on who can afford it.

Pedalling is not cycling.

Steering is not cycling.

Braking is not cycling.

Sitting on your ass is not cycling.

But put the four together...

This is where we factor in the three Rs; repetition, realism, relevance.

Repetition - do the players get lots of opportunities to repeat what you're trying to teach? Think ball each, smaller queues, smaller groups. Are there ways to get more players repeating the actions and having a go?

Realism - does it look like part of the actual game? Are the consequences and rewards that take part in football present? Do the constraints condition the players to behave in a football-like manner?

Relevance - is it useful for the players at this age and ability level?

Shooting drills are the worst for this. I've found in coaching that shooting drills tend to be where you find the most creativity and inventiveness from coaches, who find new ways to do the same old crap. New and exciting ways for players to stand in line. Inventive ways for players to receive a pass unopposed. Creative ways of serving them a pass they'd never receive in a real game.

I'm assuming in the above drill that the black player is both the server and the defender. With that in mind, I have some questions;

Why is the blue player running the width of the box before receiving?

When in a game have you ever seen a player receive a pass from the goal line to the eighteen? And if you've seen it, does it happen enough to warrant a training session?

When have you ever seen a player receive the ball on the edge of the box with pressure coming from that angle?

When have you ever seen a player receive the ball on the edge of the box with that much time and space?

Those players stood around waiting their turn, are they having fun? Are they learning anything?

This one is labelled "advanced shooting." Here's the description.

i) Player A passes the ball (inside foot) to Player B.

ii) Player B receives the ball with a touch forward and towards the end line.

iii) Player A runs around the flag (create angled run) and attacks the near post.

iv) Player B uses the "whipped" pass technique to cross the ball to Player A

v) Player A tries to shoot 1st-time from the cross if possible. 2-touch accepted if quickly taken.

vi) Players A & B switch lines and job roles.

vii) Adv, by adding a 2nd striker attacking the cross.

Realism? It's unopposed and with no decision making.

Repetitions? One shot every twelve goes, providing the cross is good.

Relevance? If you can't shoot or cross effectively while unopposed, you shouldn't be doing this drill. If you can shoot or cross effectively while unopposed, you shouldn't be doing this drill. It is somehow both too hard for novice players, and too easy for experienced players.

This drill is the atoms of football, but it's not football.

This drill is also labelled "advanced shooting."

Are the players in the centre circle trapped in jail?

Why are there mannequins instead of goalkeepers?

There are bonus points for setting up three goals, however there's too many players standing around, there's no opposition, there's no decision making, and there's no risk or reward.

At least this one has tried to include more players with passes. It's still very few shots on goal for a shooting session. Imagine teaching a kid to read a book, allowing them only one word per minute. For the other fifty five seconds of that minute, the book is closed.

Atoms, but not football.

This one, jus... why?

Parents love this kind of stuff. It looks great on Instagram. But it's useless.

"Oh but Will, you don't get it. It's a fitness session, and it just has a shot at goal at the end to motivate the players."

Right. I tore my achilles two years ago. I became stagnant and gained weight. I lost strength, stamina, flexibility. Will I get that back if I go to the gym once a week for only twenty minutes? Of course not. So why do we think kids should do twenty minutes of fitness once a week for twenty minutes? By the time you see them at training seven days later, they've already lost the minimal gains they've made. They're also no better at football for having had their time wasted by running round cones and jumping over hurdles, when they should have been playing football.

Fun and learning are tied. If they're not learning, they won't get better, and football won't be fun. If the activities aren't fun, they won't put the effort in to learn. They'll also quit by thirteen, and you'll have been their last coach. If your kids aren't fit, there's not a whole lot you can do about it with just a one hour session once a week. However, let's remember that football is fun. Football involves running, jumping, turning, accelerating, decelerating, and works on both stamina and speed. Why break these down into the individual atoms, when football does all of these things?

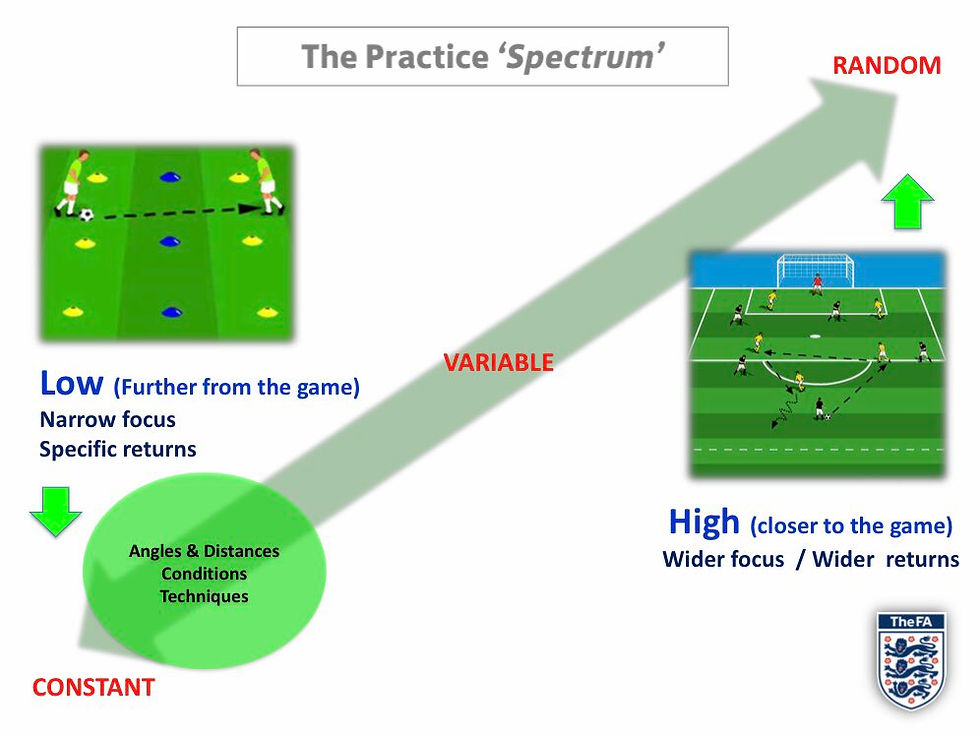

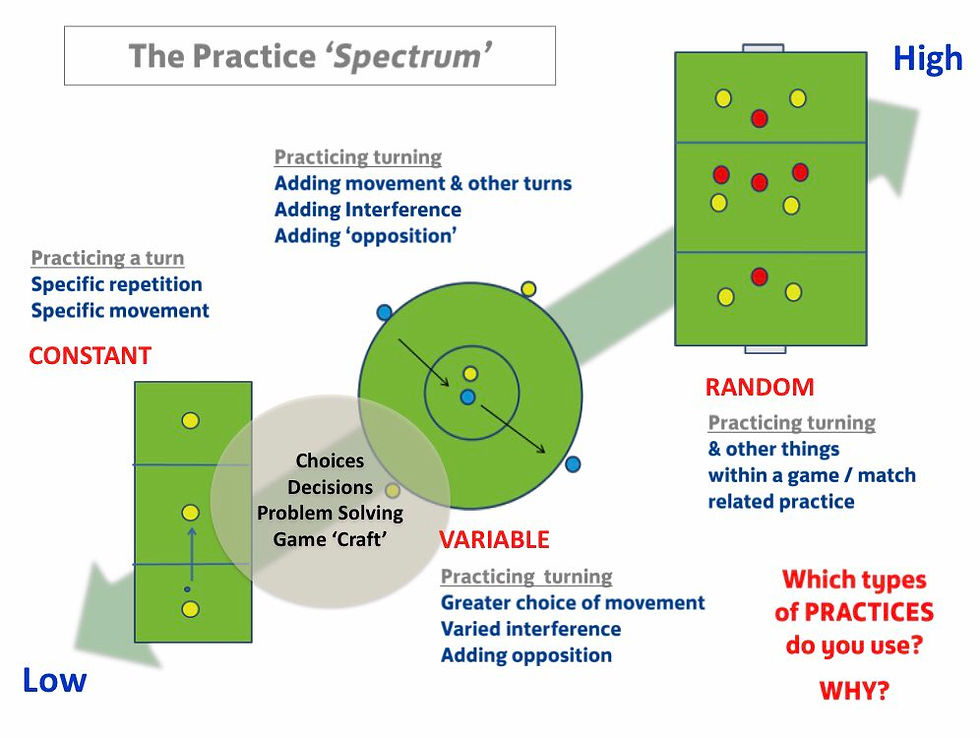

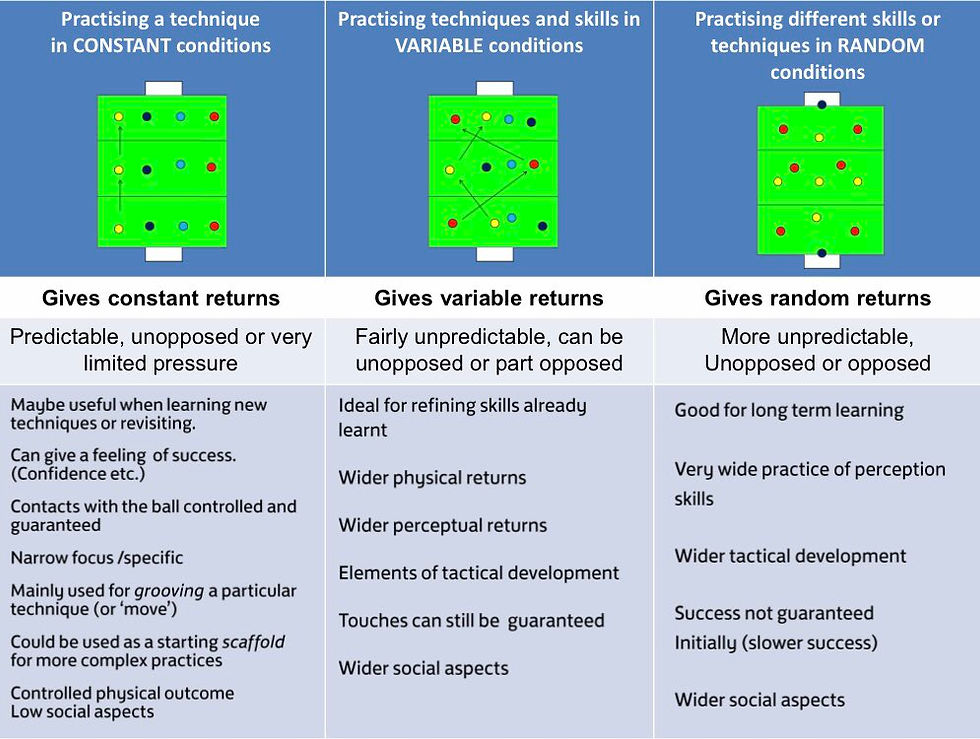

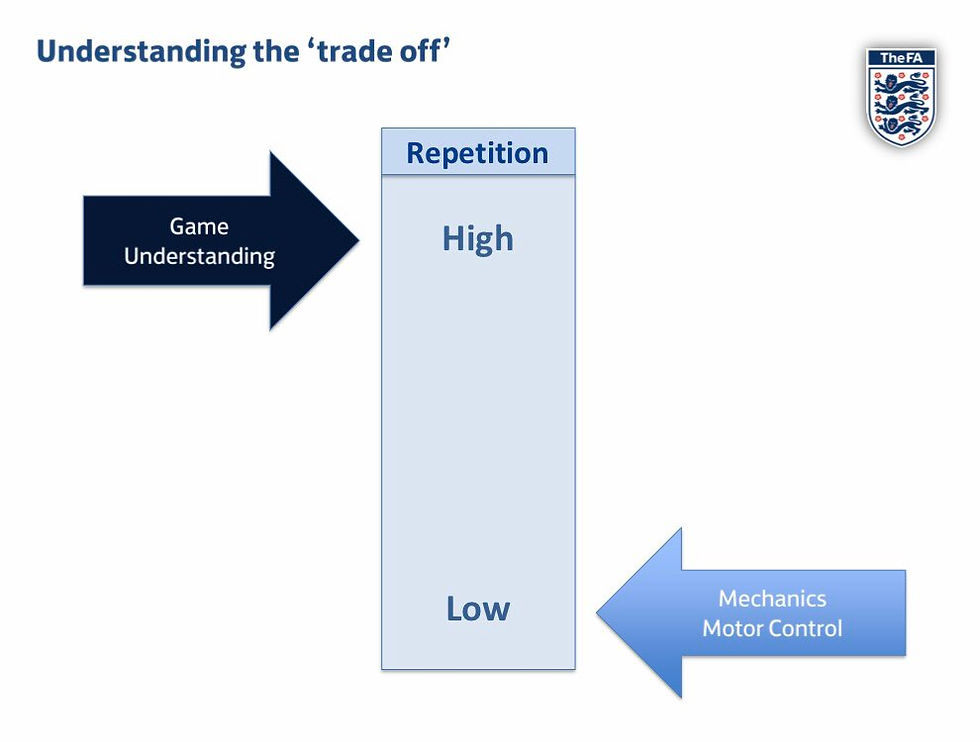

Now we need to understand the trade-off between constant - variable - random practice. It's explained really well by these graphics from the FA.

With the practice spectrum in mind, what determines where along the practice spectrum you should pitch your session? Only you can answer that. What are the needs of your players? What are the levels of ability and intelligence your players have? Inexperienced players need simpler, which is why we play 3v3 instead of 11v11. More experienced players can cope with more specific and more general ideas. So what do you need? Will it work for them?

The full game (the ocean) doesn't provide enough repetitions. Yet the individual hydrogen and oxygen atoms provide no water. There needs to be a sufficient number of molecules for there to be water, yet if there is too much water, your players will drown. And that is the skill of the coach.

Comments